The intensifying extreme heat crisis will threaten your health, your home and your wallet

In nearly every corner of the country, unprecedented heat will change the way Americans live their lives. And it's projected to get even worse.

In nearly every corner of the country, unprecedented heat will change the way Americans live their lives. And it's projected to get even worse.

There's no denying it - the last few months have been hot. This summer's unrelenting heat baked U.S. cities from coast to coast, with thousands setting new records for temperature and heat index, which also accounts for humidity. Experts at the World Meteorological Organization consider July 2023 the hottest month in Earth's recorded history, and possibly the hottest month in 120,000 years.

"It's not just that we're having some bad weather this summer," said Dr. John Balbus, Acting Director of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' new Office of Climate Change and Health Equity. "We know that this is a phenomenon associated with the overall warming of the planet."

Please type a valid zip code

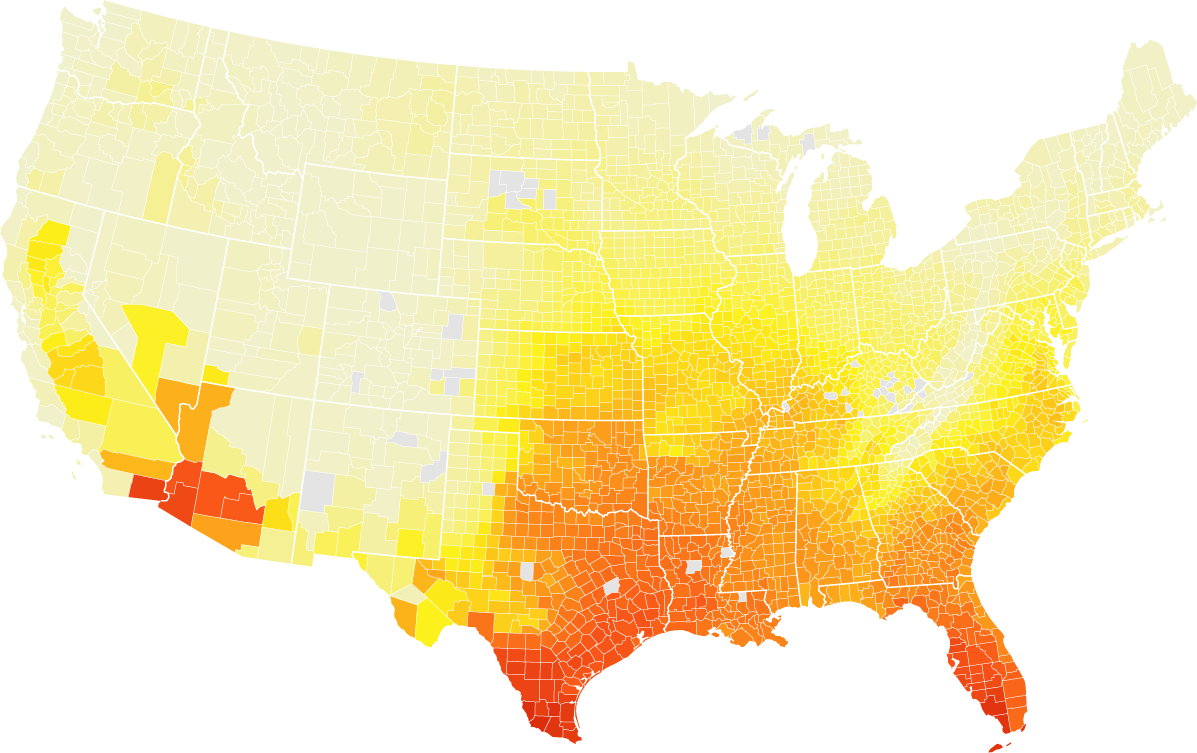

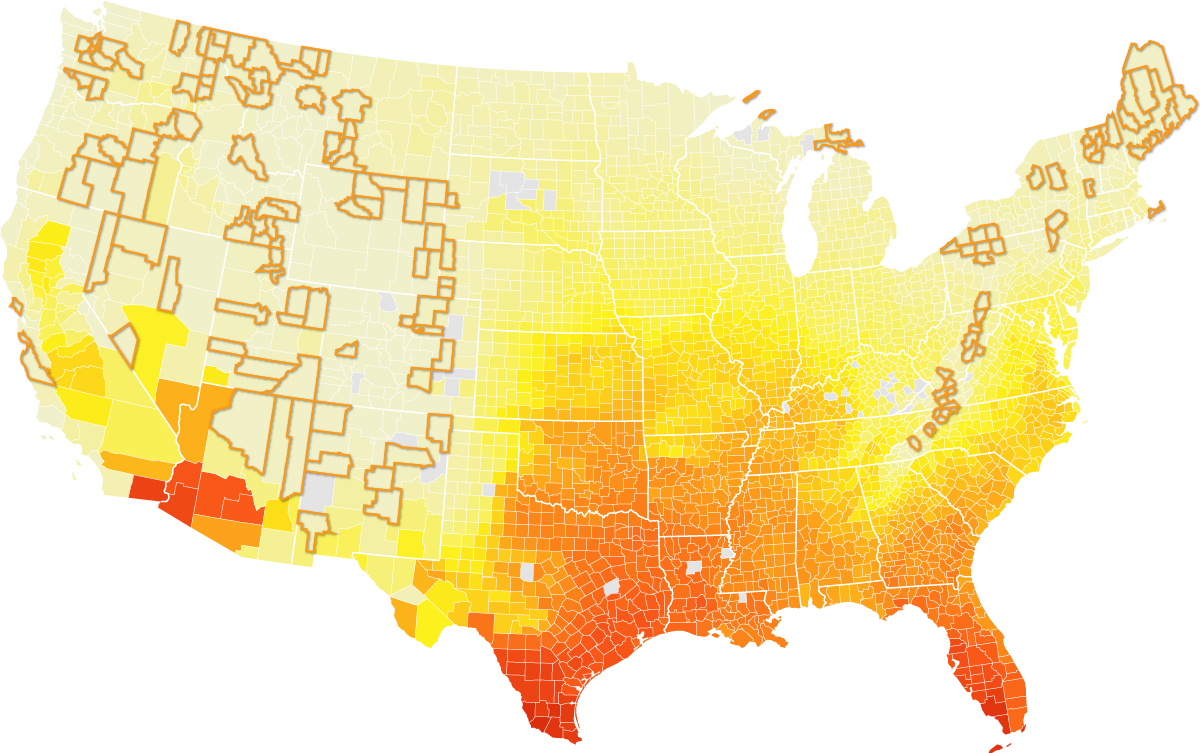

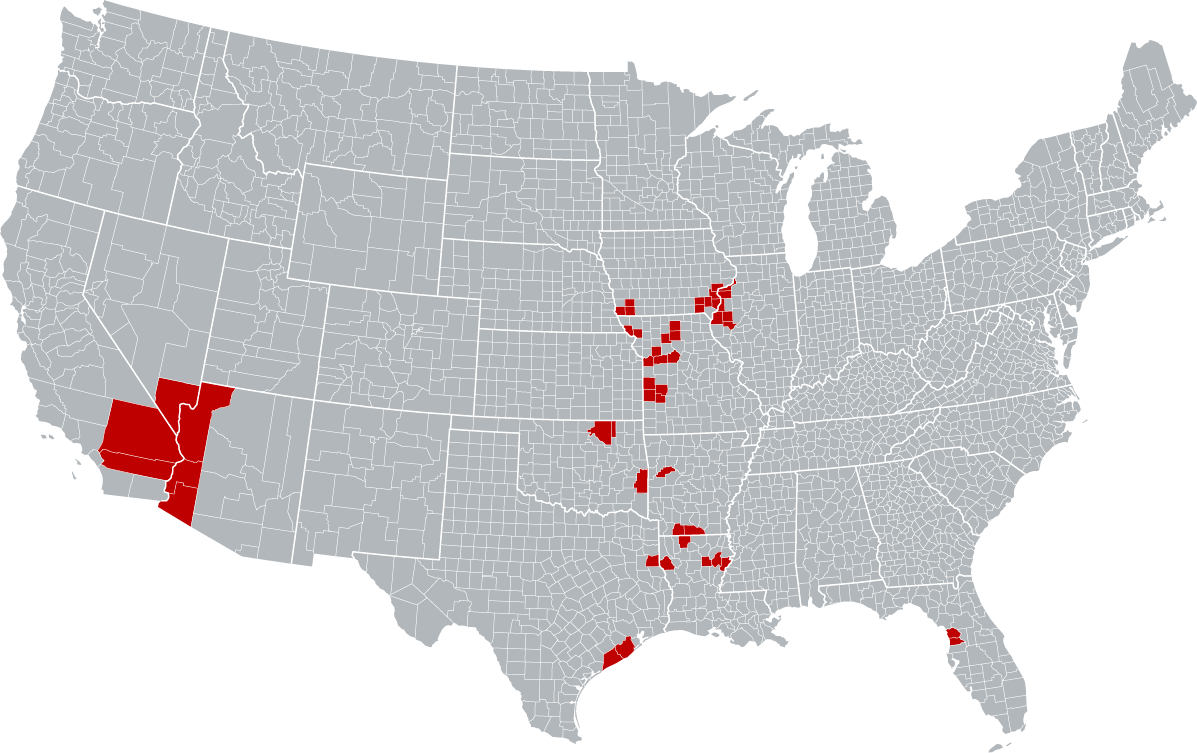

Source: First Street Foundation

In Texas alone, towns set more than 350 new temperature records in June and July. Houston experienced its first 100-degree day in mid-June, a month earlier than usual, and strung together several more in following weeks, including a 109-degree day in late June.

"June was hot. July was hotter," said Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner. "August is proving to be even hotter than July, so, it's hot."

Across Texas, residents were warned to reduce their use of power and water because the extreme demand could threaten the utility systems. And hundreds more people went to hospital emergency rooms for heat-related illnesses than did last summer.

"You can see the numbers going from a baseline in the mid-spring of maybe 20 or 50 per 100,000 emergency room visits being related to heat, to numbers over 1,000," Balbus said.

The extreme heat and its impacts lingered for most of the summer across huge swaths of the country, with previously unheard-of temperatures: San Angelo, Texas, reached a record high of 114 degrees among a string of days above 110. Kansas City, Missouri, saw a heat index of 120 degrees in July, while nearby St. Joseph reached a heat index of 122. And Phoenix, Arizona, set the record for the hottest month on record for any city in North America with a monthly average temperature - including both daily highs and lows - of 102.7 degrees.

"This phenomenon that we're seeing this summer is something that is going to be recurring, year after year," Balbus said, referencing weeks-long heat advisories and hot-tub-level ocean temperatures.

And the heat waves ahead will be even longer than those seen today, according to scientists studying the Earth's changing climate. By 2050, U.S. communities on the southwestern Texas border and the southern tip of Florida will live with more than 125 days annually - a third of the year - that feel like 100 degrees or warmer.

This phenomenon that we're seeing this summer is something that is going to be recurring, year after year.

According to the National Weather Service, days where the outdoor heat index exceeds 90 degrees Fahrenheit are considered "extreme heat days," but if the heat index exceeds 103 degrees, they become "dangerous heat days," where extended time outdoors could lead to serious health impacts.

Peer-reviewed research from the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that studies climate risk data, shows that in 30 years, the average U.S. county will see 13 more days a year with a heat index 100 degrees or higher.

In addition, 146 counties that have never seen heat indexes at or above 100 will see at least one dangerously hot day each year by 2050.

And it gets worse. Today, just 50 U.S. counties experience at least half a day with a max temperature index above 125 degrees.

In 2050, more than 1,000 counties will see temperatures this hot. At this temperature, any time spent outdoors is considered potentially harmful to human health, according to the National Weather Service.

Like San Angelo, Kansas City and Phoenix, other municipalities in the South, Southwest and Midwest will see the most days with heat indexes at or above 100 degrees in 30 years. New England and other northern states will see more extreme heat days than they do today, but the temperatures won't change as dramatically. However, research suggests these places will be more vulnerable to increased extreme heat, since they haven't had to deal with high temperatures before and don't have the infrastructure to do so.

"We can't wait for every place to have these horrible heat waves before they start taking precautions," said Dr. Cecilia Sorensen, director of Columbia University's Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education and an associate professor at Columbia's Medical Center and School of Public Health.

Houston, Texas, is no stranger to high temperatures, oppressively muggy air and long stretches of extremely hot days. According to First Street Foundation data, Harris County currently experiences an average of 69 days with a heat index at or above 100 degrees. But by 2050, the county could experience nearly 100 days of that sweltering heat.

We can't wait for every place to have these horrible heat waves before they start taking precautions.

"Climate change is real," Turner said. "And Mother Nature is not playing with anybody."

What's more, stretches of days with a heat index at or above 100 degrees could extend from about two weeks to a full month within 30 years. The city is planning for those days.

"We all have to be sensitive of the extreme weather conditions," Turner said. "We're not talking about, okay, today is 100 degrees, 103, 108, and tomorrow it's going to be a lot cooler. We're talking about each and every day where the temperature is exceeding 100 degrees."

The effects of dangerously hot days are compounded when the heat index exceeds 100 for longer than a day. In 30 years, consecutive stretches of 100-degree days could last up to 34 days longer than they do today along Florida's Gulf Coast, the First Street Foundation data shows.

On the other side of Florida, Miami-Dade County won't fare much better. The state's most populated county will experience the largest increase in the number of days with a heat index at or above 100 degrees nationwide. While Miami-Dade residents are accustomed to high temperatures, First Street Foundation data shows that within 30 years, the area will see an additional 41 days per year with a heat index above 100 - rising from approximately 50 days to three months annually. And the county could experience about 181 days - the equivalent of six months - with a heat index at or above 90 degrees, meaning residents won't get much respite from the high temperatures.

"We knew heat was a problem, but we realized that it is a significant one that deserves special attention," Miami-Dade County Mayor Daniella Levine Cava said.

Miami-Dade County is among the first local government agencies in the world to appoint a Chief Heat Officer to tackle reducing the city's carbon footprint and alleviating the effects of extreme heat, particularly on marginalized communities.

"We have zip codes where people are showing up to an emergency department [at a rate] three or four times higher than other zip codes," Chief Heat Officer Jane Gilbert said.

As the temperature gets hotter, she added, the number of heat-related deaths gradually increases.

We knew heat was a problem, but we realized that it is a significant one that deserves special attention.

"Once you get over a heat index of 90, it's a straight-line, gradual increase in the number of deaths per day that happen under high heat indices," Gilbert said. "You also get this lag effect. If you have three days in a row with high heat, and someone who is working outside every one of those days, and then coming home without air conditioning or a cooling environment, it's that exposure over time - It can be really dangerous."

Communities all around the country are vulnerable to heat for different reasons, and not only during the hottest periods, Sorensen added.

"We see impacts due to extreme heat that occur both at the extreme ends during these large heat waves, but also at temperatures that are not necessarily classified as extreme heat waves," Sorensen said. "Everyone's affected at a different temperature."

With at least 94% of counties nationwide experiencing temperatures that feel like 100 degrees or hotter in 30 years - many for the first time - experts predict unprecedented health and financial consequences.

"This is both an immediate problem - we have it right now, people are dying right now," Balbus noted, "but we know that this is going to recur - it's going to be with us next year and the year after - and that because of climate change, the temperatures are going to trend upwards over the years and decades."

Extreme heat is more than just uncomfortable: sustained hot temperatures threaten communities' health and safety.

Heat is already responsible for the most deaths nationwide from a weather hazard, according to the National Weather Service. From 2001 through 2010, about 6,000 Americans died as a direct result of the heat, a cumulative rate of about 1.9 deaths per 100k people, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows. The following decade, 2011-2020, saw over 8,200 heat-related deaths nationwide, with a rate of 2.5 per 100k. As the U.S. sees more dangerously hot days, experts predict this rate will increase.

Dr. Sorensen studies the intersection of climate change and human health. She said global warming is already taking a toll on Americans' wellbeing.

"We start seeing impacts even with small rises in temperature," Sorensen said. "At one degree Celsius above average seasonal temperatures, vulnerable patients start getting affected."

In 2019, the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality's Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project tracked 80,000 emergency room visits directly related to heat across 39 states and Washington, D.C. Sorensen has seen this phenomenon firsthand.

"I always brace myself going into an ER shift when it's hot out," she said. "If you're going to have a really hot week, towards the end of the week, we're going to start seeing huge, huge numbers of people coming in."

Heat-related illnesses range from painful to life-threatening, according to Dr. Lara Phillips, an Emergency Medicine physician at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. She has seen an increase in visits for these conditions in recent years, starting with mild heat-related cramps and then progressing to heat stroke.

Milder heat-related emergency department visits can be for issues like swollen limbs, fainting, dehydration and heat rashes.

More moderate heat-related illness comes in the form of heat exhaustion, with symptoms such as high body temperature and faster breathing. Phillips added that some people may feel dizzy or have a bad headache.

The deadliest form of heat-related illness is heat stroke, when a person's core body temperature rises above 103 degrees.

"At that point, your cellular processes cannot function," Sorensen said.

Someone with heat stroke may seem confused or stop making sense. Their organs will begin to fail, and they will need to be cooled down to a normal body temperature within 30 minutes to prevent irreversible damage. Without treatment, almost 80% of people with heat stroke die from it.

But when examining mortality associated with heat, Sorensen said, "It's not just the heat stroke deaths that we're looking at. What we see when there's heat waves is that there's a massive increase in all types of morbidity and mortality."

These additional types of mortality include existing heat-sensitive conditions, mental health concerns and even serious injuries.

"When you're exposed to heat, your cognition isn't as good, you're more likely to have accidents, slips, falls, motor vehicle accidents," Sorensen said.

Heat is also associated with sleep disturbances, learning difficulties and increased violence, Balbus noted. And heat exposure can contribute to severe pregnancy-related blood pressure conditions and preterm births, Sorensen added, threatening healthy pregnancies and increasing both maternal and infant mortality.

Heat is particularly strenuous on the heart, lungs, kidneys and brain, so heat waves can be deadly to people with chronic cardiac or respiratory disease and trigger acute health issues like kidney failure or stroke. Even common conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure put people at greater risk for heat-related health impacts, Sorensen said. More than one in 10 Americans have diabetes and nearly half have high blood pressure, National Institutes of Health and American Heart Association data show. Many common medications can also make people heat-sensitive.

For those who are vulnerable to heat, temperatures don't need to be extreme to be dangerous. Phillips remembers a patient with a fever and confusion coming into one of her hospital's community sites in South Philadelphia.

"It was hot outside, maybe upper 80s, but not the hottest it's been," she said, explaining the medical team didn't initially suspect heat-related illness. "This person was elderly, they're on multiple medications, they live by themselves, their apartment didn't have access to air conditioning, and they were very sick," Phillips said.

These risk factors changed their calculus: The patient was suffering from heat stroke, and he needed to be cooled down immediately. He ultimately went to the intensive care unit and with help, he recovered.

When you're exposed to heat, your cognition isn't as good, you're more likely to have accidents, slips, falls, motor vehicle accidents.

Societal factors also affect vulnerability to heat-related health impacts, with low-income families and some communities of color - particularly Native Americans - at increased risk. Lack of access to housing with air conditioning poses risks as well.

"Just like you can have food deserts, where people don't have access to the freshest produce, you can similarly have areas that don't have access to good cooling systems," Phillips said. "And these areas are not uncommonly those with potentially lower socioeconomic status."

Individuals should know their specific risk factors to prevent heat-related health issues, Phillips said. There are ways to reduce the chance of heat-related illness, including staying inside during the hottest times of day, wearing light clothing and sunscreen, and drinking plenty of fluids. But vulnerable populations can become ill even when taking these precautions.

Last summer, Sorensen saw a 75-year-old man come into the emergency room after his family found him unconscious in the backyard. He had been clearing brush all day, but said he had taken rest breaks and drunk lots of water. He grew up in Central America, so he knew about the dangers of heat, he told Sorensen. Despite these safeguards, he was still susceptible to heat exhaustion and heat syncope.

"People think they know what to do when it's hot out," Sorensen said. "But the heat we're experiencing is like nothing we've ever seen."

Communities that have not previously experienced extreme heat may see even more severe health impacts.

"It can affect people across age, gender and health lines," Phillips added. "And it's a prevalent problem."

Currently, American health systems tend to take a reactive approach to extreme heat, scrambling to protect vulnerable populations as a heat wave descends upon them, Sorensen said. But as these become more common, preventing health effects will require a proactive approach.

"We need more comprehensive, thought-through plans," she said, "because this century is gonna get really, really hot."

When temperatures soar, business productivity plummets.

Approximately 4.3% of American workers spend at least two-thirds of their day outside, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. But when heat indexes get to extreme or dangerous levels, outdoor workers need to take more breaks or halt work for hours at a time.

Peter Elwin, Head of Food and Land Use for environmental think tank Planet Tracker, studies the effects of extreme heat on economic centers. By 2030, he says, productivity will decrease by at least 0.21%, the equivalent of about 389,000 full-time jobs.

"There's absolutely no way you can be on a construction site when the temperatures are sort of getting up that high. It just has to close," Elwin said. "You can't be going around and repairing somebody's plumbing, can't be doing electrical work. All the infrastructure, repairing the roads. So things quite quickly grind to a halt in terms of maintenance and repair."

In Colorado, Sorensen saw a 36-year-old agricultural worker in the emergency room. He had been driving a tractor around hot fields for 12 hours, and when he came back to the worksite people found him very confused. They brought him to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with heat stroke.

Sorensen's patient is not alone in his experience. Mayor Turner of Houston said outdoor workers in his city don't have any option but to work in the heat – but that doesn't mean they can't be protected.

"If you, for example, are a solid waste worker, you have to be out there. If you have to be out there filling these potholes or repairing these streets, you can't do that remotely," Turner said.

Turner added that the Texas governor signed a bill into law this June that would eliminate mandatory water breaks for outdoor workers.

"And can you imagine they did that this year?" Turner said. "In a year in which, across the country - quite frankly, across the globe - we are facing extreme heat conditions."

At the national level, Sorensen said lawmakers need to do more to protect workers.

"There's currently no federal standards to dictate when people should stop work at different temperatures," despite workers compensation claims increasing with exposure to heat, Sorensen said. "We need strong guidance from the federal government that applies to all industries, outdoor laborers, including agricultural workers, construction workers, but also thinking about indoor heat stress."

Balbus agreed, calling for a federal "heat standard" requiring employers to protect their workers from the dangers of extreme heat through access to water, breaks and cool environments.

There's currently no federal standards to dictate when people should stop work at different temperatures.

For indoor workers, businesses will have to hike their utility budgets to keep inside temperatures comfortable enough for workdays.

"If you're in some sort of, you know, relatively high-tech environment, your PC and laptop, whatever, it's all generating heat," Elwin said. "So you've actually got a heater on your desk, which is fighting the air conditioning unit above your head or below your feet."

According to the First Street Foundation, by 2050, U.S. residential and commercial properties will spend $288.5 billion more on air conditioning than they do now.

"Economically, that begins to bite," Elwin said.

Extreme heat events could even impact the existing infrastructure of cities, Elwin added, especially those not built to withstand high temperature events. He explained that roads could close because of soft asphalt or increased potholes, and railroad tracks could buckle, all causing bottlenecks in the supply chain.

"You could literally see a business go out of business in that sort of circumstance if they were, you know, unusually badly prepared, or just had a very tight supply chain," Elwin said. "It could be the ending of them."

Experts agree: The effects of extreme heat are not equally distributed. In order to create resilient cities, they say officials need to focus on mitigating urban heat islands - areas with lots of asphalt, concrete and tall buildings with fewer green spaces, often found in low-income communities of color.

"Communities that have been historically redlined have been demonstrated to have higher degrees of air pollution and also worse urban heat islands and higher levels of heat exposure," Balbus said, adding that some groups are also more sensitive to the heat: "isolated elderly, children, if they're left exposed, can be more vulnerable."

Some health systems have used medical data to identify these at-risk patients and sent transport to bring them to cooling centers, Balbus added.

"The people who are most likely to suffer in the heat are the people who, for example, can't afford to pay their electric bills and have cooling," he said. "Or the people who are experiencing homelessness or who are experiencing severe mental health disorders. They are dying disproportionately and suffering disproportionately in these heat waves."

In theory, these deaths are preventable, Sorensen added. But averting them is difficult and will take a whole-system, proactive approach focused on communities that bear the brunt of our warming climate.

Page development: Grace Manthey | Data analysis and reporting: John Kelly, Mark Nichols, Grace Manthey, Frank Esposito, Lindsey Feingold, Maggie Green, Maia Rosenfeld | Visual content producer: Adriana Aguilar | Video producers: Justin Allen, Christopher Drew | Digital production: Rachel Schwartz, Alex Meier, Margeaux Jimenez, Kristen Hague

Ⓒ 2023 ABC Owned Television Stations